A Grand New Connection: LIRR to Grand Central Madison

“The crucial factor for transportation in this region is the interdependence of city and suburb – interdependence today, the even greater interdependence tomorrow.” – Metropolitan Transportation – A Program for Action, 1968

“Even while Walt Whitman was romanticizing the Brooklyn Ferry, daring minds were planning permanent linkages between thriving Manhattan and the growing communities of Long Island.” – Threshold to the Seventies, 1972

Introduction

When the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) was chartered on April 24, 1834, railroads had been in existence for only nine years and Long Island was sparsely populated. Today, America’s oldest railroad still operating under its original name is also the busiest commuter railroad in North America. In the 1830s, Long Island’s 70,000 residents were mostly concentrated in Brooklyn and Queens, the island’s western end. The LIRR became inextricably linked to the development of Long Island and the surrounding metropolitan area. Direct service from Long Island to Manhattan’s west side began with the opening of Pennsylvania Station in 1910. Today, the four counties on Long Island are home to 7.88 million people – one-third of the entire population of New York State – and the LIRR is a vital link in the regional transportation network.

The opening of Grand Central Madison is one of the most seismic shifts in New York transportation history, allowing LIRR trains to provide service directly to Manhattan’s east side. The terminal itself is only one aspect of potentially the largest transit improvement project ever in the northeastern United States, East Side Access, which encompasses building miles of new track, reconfiguring and updating rail yards in New York City and Long Island, modernizing infrastructure such as bridges and tunnels, and the hiring of thousands of new employees.

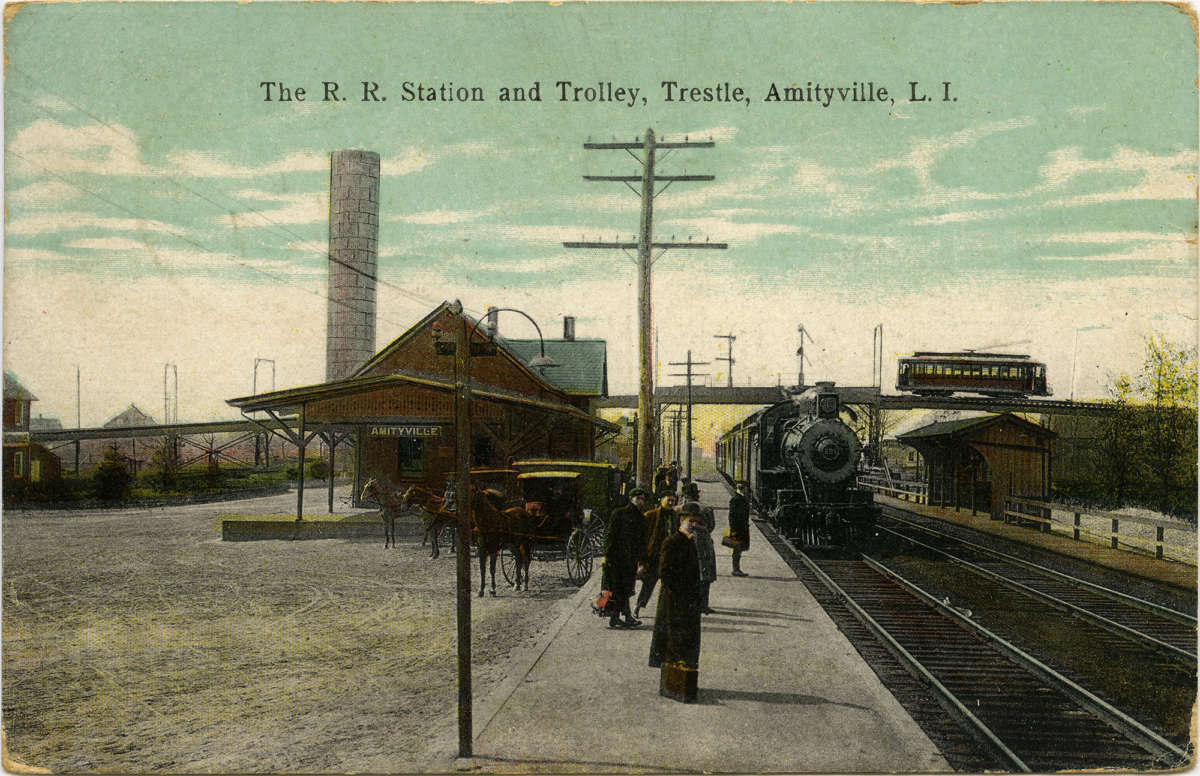

The R.R. Station and Trolley, Trestle, Amityville, L.I., 1911

New York Transit Museum Postcard Collection

2011.35.10

In the early 1900s, the areas around Long Island Rail Road stations were bucolic. Today they are often bustling hubs of activity.

R.R Station and Library Hall, Mattituck, L.I., c. 1910s

New York Transit Museum Postcard Collection

2012.7.9

Grand beginnings

In 1837, as rail travel was beginning to take root and re-define the American landscape, The New York and Harlem Railroad (NY&HRR) built the first rail structure on the Grand Central site, a car maintenance barn. The New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad (NYNY&H), chartered in 1849, used the NY&HRR tracks for service between Wakefield in The Bronx and Manhattan. The Hudson River Railroad operated on the west side of Manhattan and had a depot in Madison Square. Although railroads expanded travel beyond the confines of Manhattan, steam locomotives and their concomitant noise and dirt caused consternation amongst Manhattan residents, who pressured the city to curtail their use. Eventually, steam locomotives were prohibited from traveling south of 42nd street, which encouraged the NY&HRR to buy more real estate around their car barn and expand their facilities.

Grand Central Depot, 1871

New York Transit Museum Metro-North Collection

2001.31.132

Between 1863 and 1867, Cornelius Vanderbilt gained control of the NY&HRR, the Hudson River Railroad, and New York Central Railroad and consolidated them into the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad in 1869. He then built a connecting line along the Harlem River’s northern and eastern banks, running from the Hudson River Railroad in Spuyten Duyvil, Bronx, to the junction with the Harlem Railroad in Mott Haven, Bronx, as part of the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad.

This not only set the stage for Vanderbilt’s wealth and power via transcontinental railroads, but for a transportation hub in Manhattan where all his railroads could converge.

Grand Central Depot, which opened in 1871, was expected to reach capacity by the 1890s, but it only took until the mid-1880s for its 12 tracks to fill. An annex was built in 1885 with an additional 7 tracks. By 1897 it was at capacity again.

Razing brownstones for Grand Central Terminal, 1906

New York Transit Museum Lonto / Watson Collection

2010.20.20.40.28

Train traffic increased in the 1890s, but so did the problems they caused: soot, smoke, noise, and accidents. In 1903, after several fatal accidents involving steam locomotives, a law was passed mandating rail companies to phase out steam and become electrified.

A plan was hatched to rebuild Grand Central as a terminal with separate levels for commuter and intercity railroads, a main concourse with ramps to the lower concourse and the IRT subway station, and an expansive waiting room.

Grand Central Terminal under construction, 1912

New York Transit Museum Metro-North Collection

2001.31.20

In 1913, Grand Central Terminal was opened to provide expanded service for these and other rail lines. From its glorious opening, initial heyday, decline, and rebirth, Grand Central Terminal has provided critical service for points north and west of New York City.

1960s: The Program for Action sets the stage

Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) service has terminated at Pennsylvania Station since 1910. Although plans to bring LIRR service into a second terminal on Manhattan’s East side have existed for more than a century, the possibilities for the project’s scope and impact beyond New York City and Long Island were not fully conceptualized until the 1960s.

In 1964, a new Federal law called the Urban Mass Transportation Act provided matching funds for large-scale transportation improvements. In response to this, the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority (which had been chartered in 1965 to take over the operations of the LIRR) published a report in early 1968 entitled “Metropolitan Transportation – A Program for Action”, a multi-year, multi-billion dollar plan to improve transportation in the New York City area. This report was the blueprint for using the Federal money, and later that year New York City received $25 million of an anticipated total of $254 million. This was the first major federal investment in New York’s subways, and the MCTA dropped the “commuter” in March of that year, becoming the MTA.

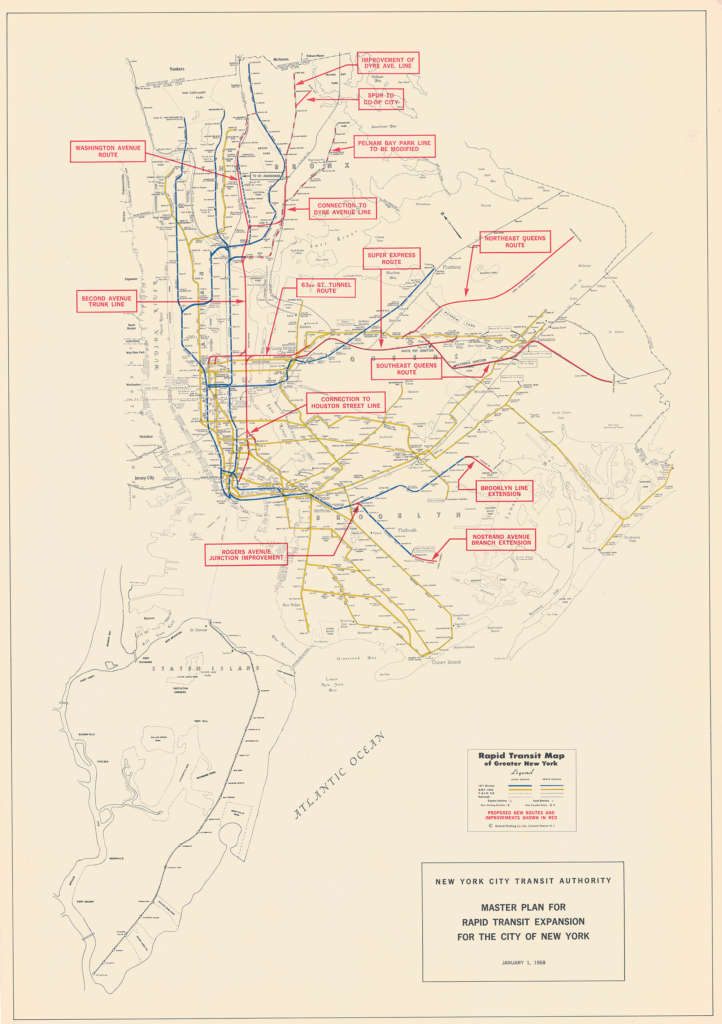

Master Plan for Rapid Transit Expansion for the City of New York, January 1968

New York Transit Museum Collection

2005.42.2

This map shows the scope of the Program for Action as proposed in early 1968. In addition to improvements to subways and bridges, the plan had numerous aspects that would benefit the LIRR.

These included:

- Metropolitan Transit Center: a blocklong development containing a new LIRR East Midtown terminal ($195 million), a terminal for high-speed access to Kennedy Airport, bus and taxi service, pedestrian access for Lexington Avenue Line and Second Avenue Subway, Penn Central, New Haven

- Extension of LIRR into Lower Manhattan

- Improvements to Grand Central and Pennsylvania Station

- Direct link to JFK from a modernized Jamaica station

- New transit centers along Main Line: Hicksville, Pine Aire, and Ronkonkoma (MacArthur Airport)

- Purchase of almost 900 new railcars

- Extend electrification of Port Jefferson line, Pinelawn to Ronkonkoma, and Bethpage to Patchogue

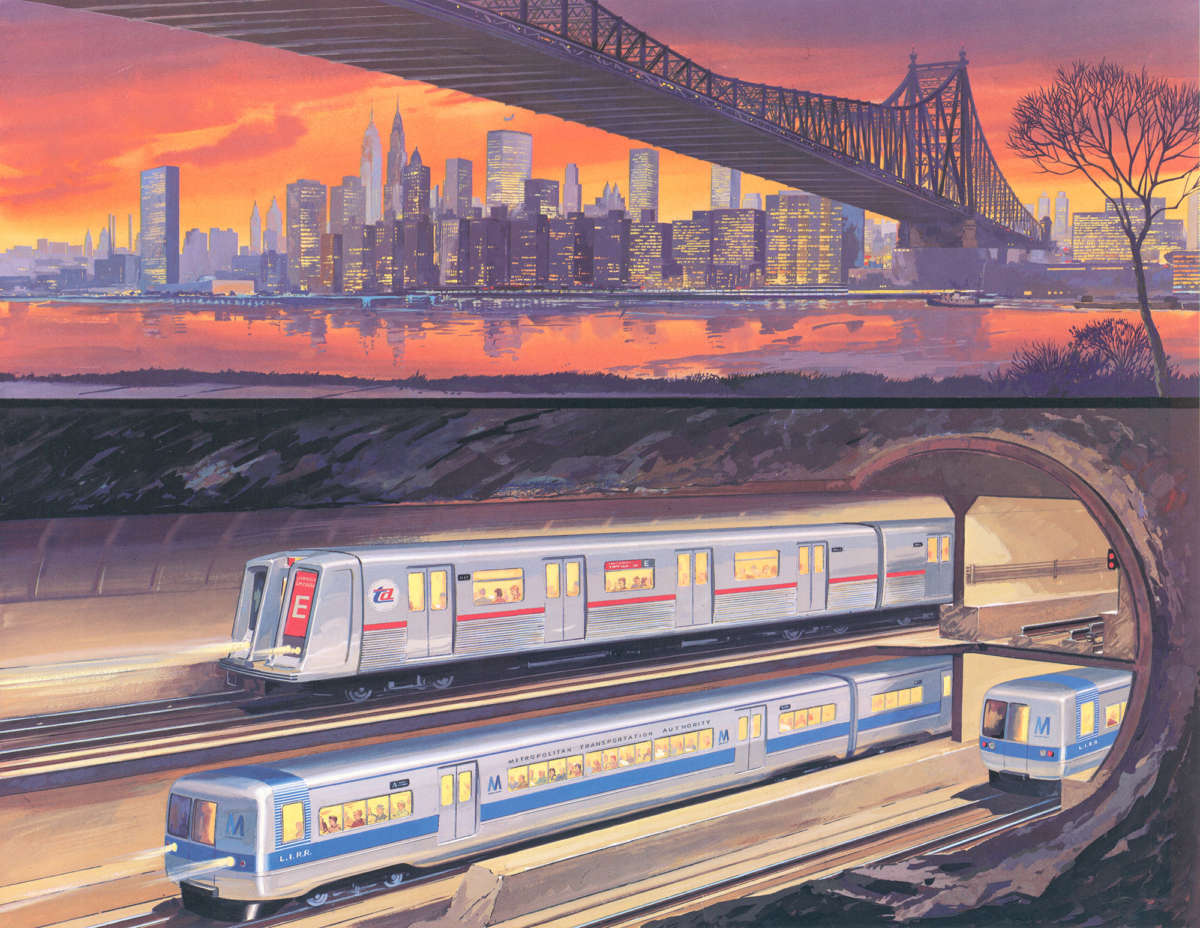

Artist’s rendering of the 63rd Street Tunnel, c. 1968

Painting by John Gould

New York Transit Museum Collection

John Gould’s rendering of the future 63rd Street Tunnel, complete with R-40 subway cars and LIRR M-1 “Metropolitan” cars (the newest rolling stock at the time) appeared in the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority’s 1968 report “Metropolitan Transportation – A Program for Action” which laid out a plethora of transit and infrastructure projects that aimed to correct past shortcomings and attempted to future-proof the service area. The tunnel’s projected cost was $69.5 million dollars, shared equally by New York City and New York State.

63rd Street Tunnel groundbreaking, 1970

New York Transit Museum NYCTA Photograph Unit Collection

2005.48.11

New York’s governor Nelson Rockefeller and New York City mayor John Lindsay were among the dignitaries who broke ground on the Queens side of the tunnel in 1970.

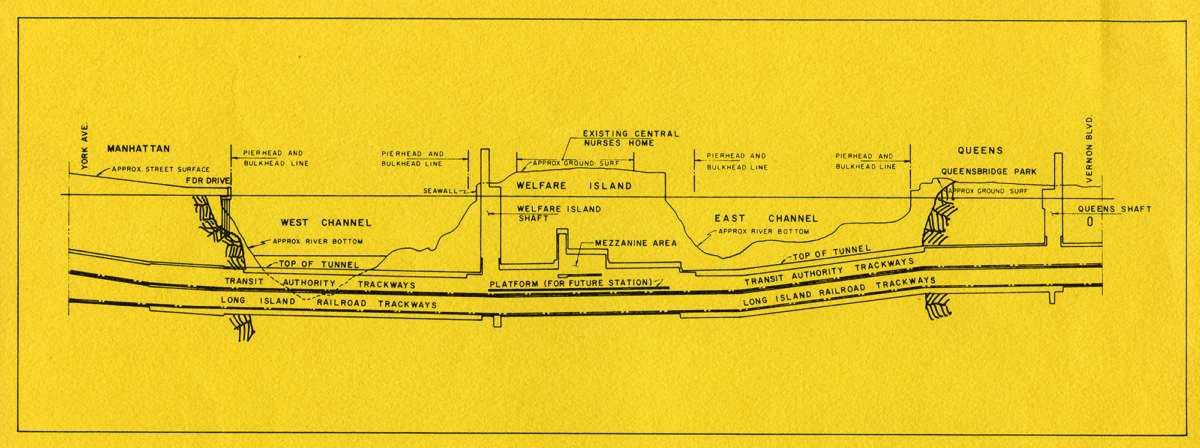

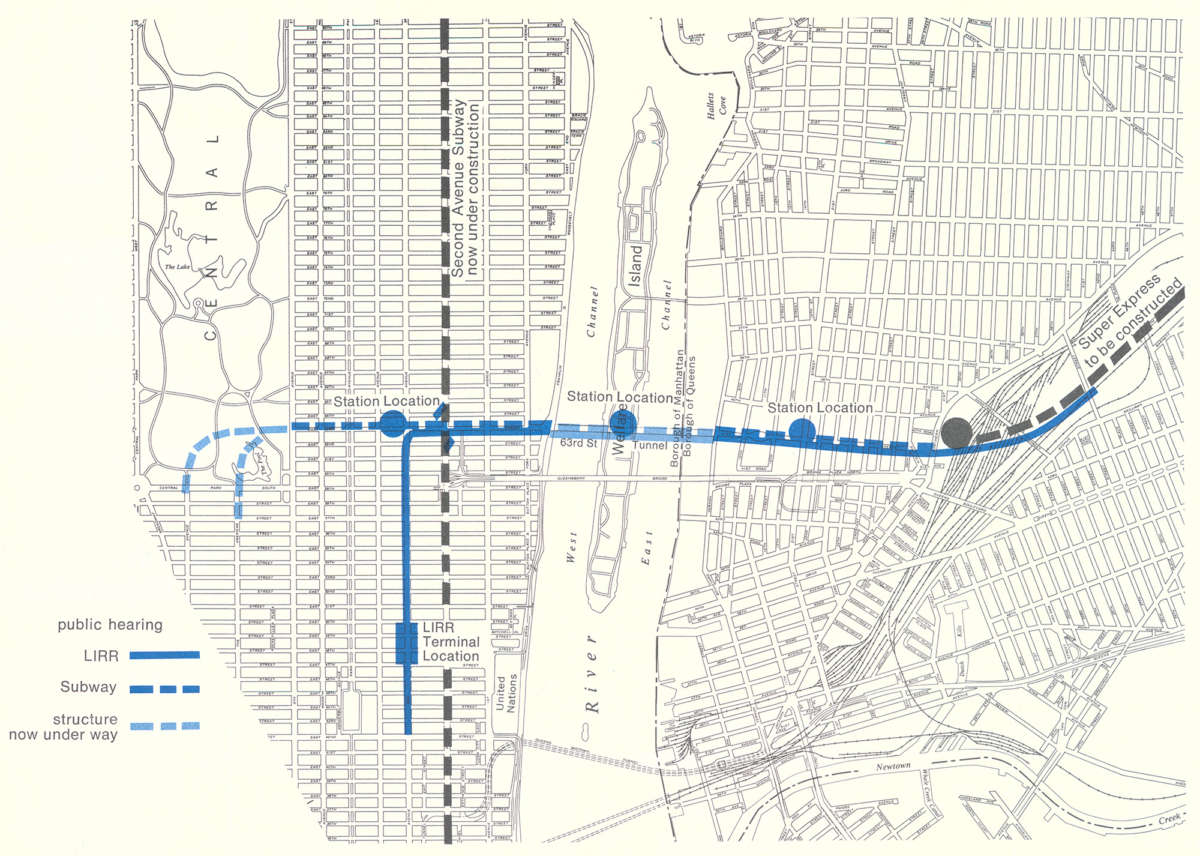

Diagram of 63rd Street Extension project, 1972

New York Transit Museum Collection

2004.19.336

In 1972, while the 63rd Street tunnel was being built, the Authority considered a smaller version of the Program for Action’s plans for the LIRR expansion, as shown in this map. The proposed 48th Street terminal met with opposition, especially because it was thought that Grand Central Terminal could handle the extra capacity. Brochures and public hearings were part of the informational campaign.

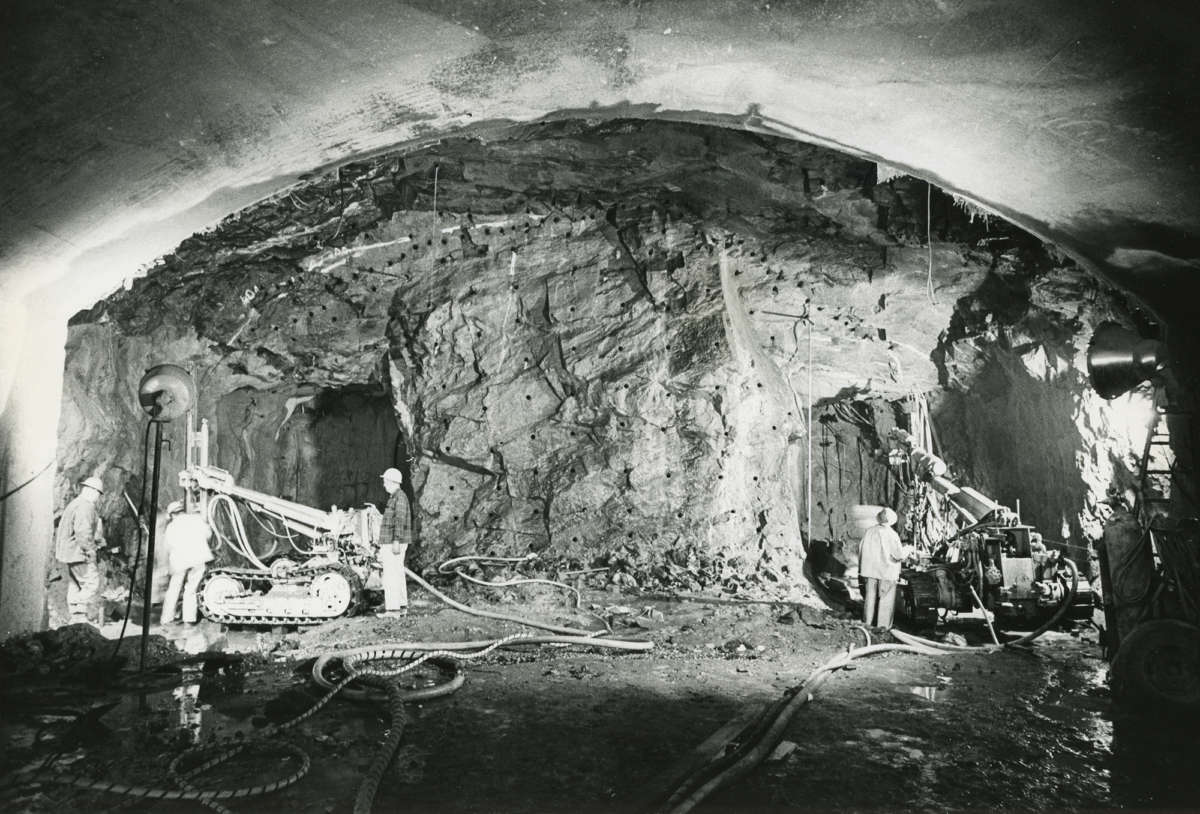

East Side Access tunnel excavation, 1972

Photograph by Steve DiSanto

New York Transit Museum Lonto / Watson Collection

2010.20.14.56.7

Excavation of the 63rd Street Tunnel was long and arduous. Construction officially began in November of 1969, but the fiscal crisis in 1975 brought the LIRR level to a halt – and stalled expansion plans for the railroad. The subway tunnel was completed because it was deemed more expensive to leave it unfinished than it was to complete it. This earned the lower portion of the tunnel the nickname “The Tunnel To Nowhere.”

63rd Street Tunnel holing through ceremony, 1972

New York Transit Museum Subway Construction Photograph Collection

R131AS1_z904

Governor Rockefeller, Mayor Lindsay, and William J. Ronan, chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, gathered under Roosevelt Island to celebrate the “holing through”, or connection between both the Manhattan and Queens sides of the tunnel.

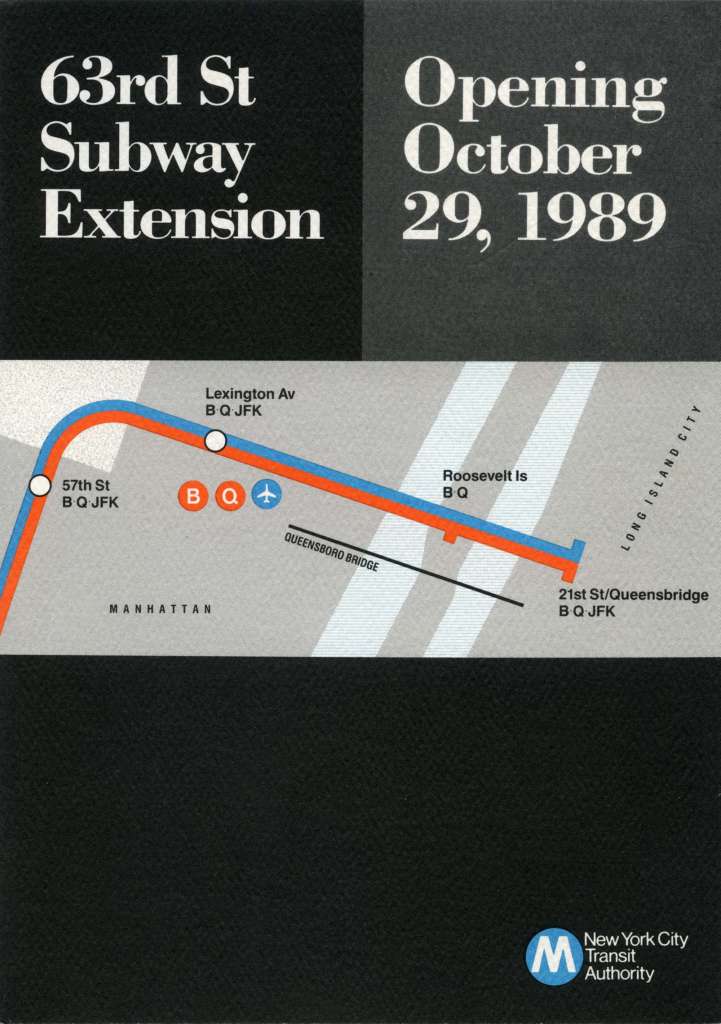

63rd Street Extension opening invitation, 1989

New York Transit Museum Collection

On October 29, 1989, the 63rd Street Extension opened. This included the 63rd Street Tunnel and three new subway stations: Lexington Avenue–63 St, Roosevelt Island, and 21 Street–Queensbridge. More than 30 years after its proposal, a key piece of the future East Side Access project was in place.

Introducing the New 63rd Street Extension, 1989

New York Transit Museum Collection

2544

Only one part of the 63rd Street Tunnel – the upper level – opened in 1989 and is used for the IND 63rd Street Line (F train). The lower level, which opened in 2022, is used by Long Island Rail Road.

1990s – 2000s: Modernizing a 188-year-old lifeline

Though the 63rd Street Tunnel is the means through which Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) service is delivered to Grand Central Madison, it is only a small part of the massive East Side Access project. The project aims to ease crowding at Pennsylvania Station as well as on Queens subway lines, reduce traffic congestion, modernize rail infrastructure, attract new ridership to public transportation, and strengthen intermodal connections. In short, it will modernize the 188-year-old railroad with the most significant work to its infrastructure in more than a century.

In 1992, the MTA completed a study underscoring the fact that Pennsylvania Station’s physical constraints precluded it from accepting the increase in service the growing ridership of the LIRR demanded, and the plans to build a new terminal on the East side of Manhattan began anew. In 1998 the decision was made to plan and complete the project, and construction began in 2001.

Before construction of Grand Central Madison could begin in earnest, numerous other smaller projects on Long Island (as well as The Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn, and Manhattan) had to be planned or completed. These included the purchase of new rolling stock for both the LIRR and the Metro-North Commuter Railroad, improvements to Pennsylvania Station such as the Moynihan Train Hall and concourse, lengthening platforms, expansion and improvements to LIRR storage yards and maintenance shops, and adding a third track to the LIRR Main Line.

Manhattan: New caverns

Although construction methods and equipment have become more efficient over the years, digging a rail tunnel still takes a lot of time and money. To connect the 63rd Street Tunnel to the new terminal at Grand Central, two 22-foot Tunnel Boring Machines (TBMs) excavated approximately 25,000 linear feet of tubes under Manhattan. This work began in 2007 and ended in March 2013. The Manhattan tunnels weren’t alone: four new tunnels were excavated under the Sunnyside Yard and Harold Interlocking in Queens.

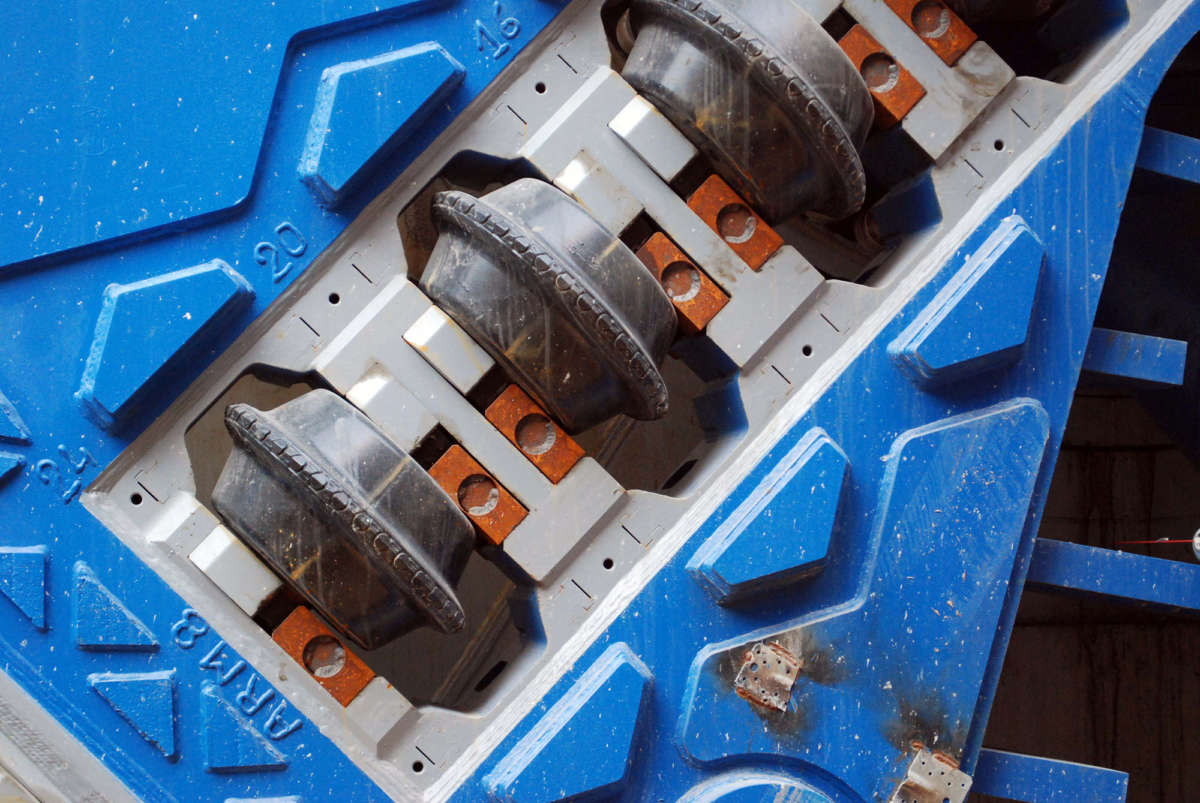

Cutting “teeth” of the Tunnel Boring Machine, 2011

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

A TBM is like a giant, mechanical worm. After the cutting disks pulverize the rock, it exits the rear of the machine on a conveyor belt.

Some of the crushed rock (called “spoil”) from the East Side Access tunnels was used to fill in Sunnyside Yard and the Harold Interlocking.

Worn out TBM “tooth”, 2011

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Cutters on the TBM wear out and need to be replaced. Here, a worker shows how worn down the cutter has become.

TBM excavating under Grand Central, 2009

Photograph by Patrick Cashin

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Applying shotcrete, 2011

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Shotcrete is one of the many layers of tunnel and station construction, used to smooth raw edges and add support. Shotcrete is a special kind of mortar that is applied by forcing it through a hose with compressed air. This spreads and compacts it at the same time and enables it to be placed evenly on surfaces of any shape, such as curves. Steel mesh reinforcement adds stability.

Preparing for a controlled blast, 2013

Photograph by Patrick Cashin

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Workers use drill and blast mining where a TBM is not cost effective or physically possible, such as tight curves. Holes are drilled in a pattern designed to remove the most rock, in manageable pieces, with the smallest explosive charges. Under careful monitoring, each charge is detonated sequentially in short bursts to spread the energy from the explosives over a long period of time. This minimizes ground vibration, which could damage nearby structures. Seismic monitors track the impact of these explosions.

Installing waterproofing, 2011

Photograph by Patrick Cashin

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Manhattan: Building a new terminal

Grand Central Madison, at 700,000 square feet, is the largest mined underground rail station in the United States and has parts as deep as 180 feet below street level. When the East Side Access project was first proposed, a terminal at Third Avenue and 48th Street was considered, but in the 1970s it was decided that Grand Central Terminal would be a better location for LIRR service.

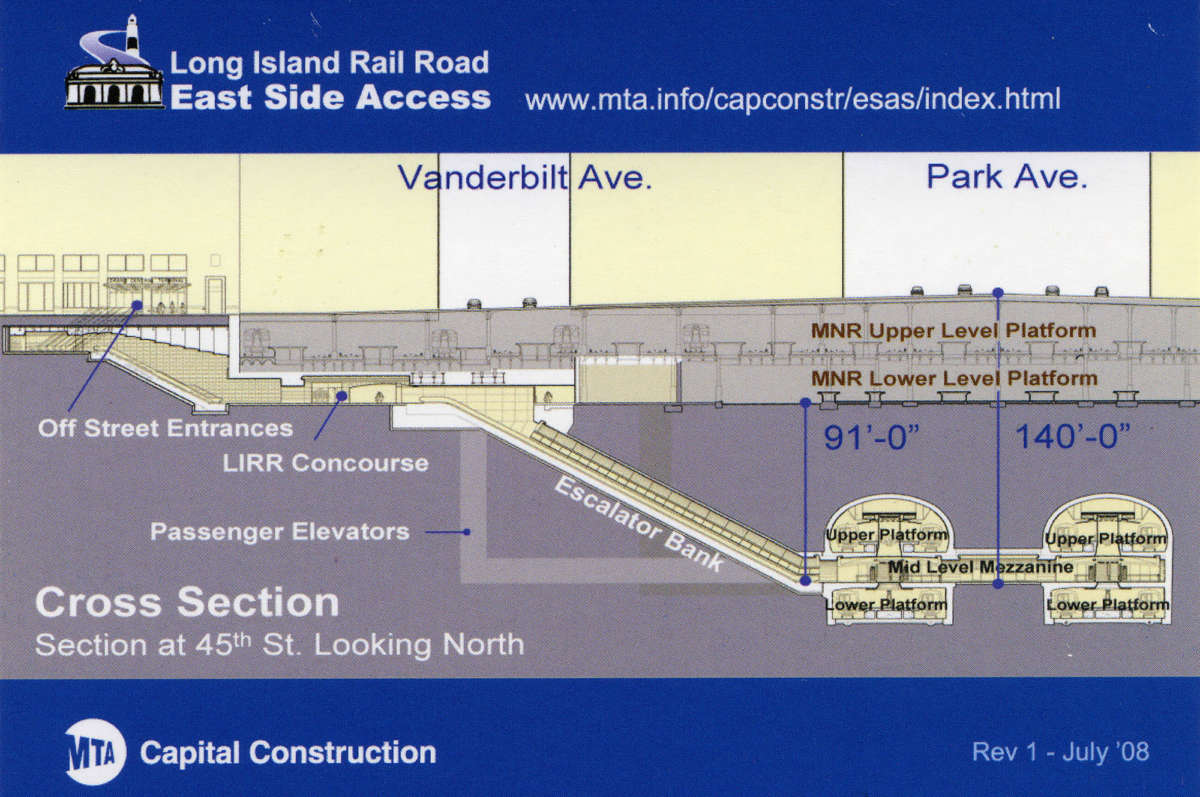

LIRR structures at Grand Central Terminal, 2008

New York Transit Museum Collection

Gift of Jack W. Boorse

2016.38.93

This 2008 info card showed customers where the LIRR platforms would be once the project was finished.

Installing rebar in the GCT cavern, 2013

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

The LIRR tracks that serve Grand Central Madison are 180 feet below Park Avenue, and 90 feet below the Metro-North tracks.

Groin rib structure, 2017

Photograph by Trent Reeves

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

A groin vault is a type of architectural structure that is incredibly strong but uses less materials than a typical barrel vault. It was first used by the Romans, and its efficiency in distributing pressure makes it a good choice for underground train stations, especially one as deep as Grand Central Madison.

Passenger concourse, 2019

Photograph by Trent Reeves

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Grand Central Madison’s passenger concourse is about 50 feet below street level. Some of the design elements echo those of the decommissioned City Hall station on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line (built in 1904) and, of course, Grand Central Terminal.

Grand Central train yard under construction, 1917

New York Transit Museum Metro-North Collection

2001.31.79

The main concourse of Grand Central Madison is built where the Madison train yard used to be, shown under construction in 1917. A new maintenance facility at Highbridge, The Bronx, opened in 2003 and has replaced it.

Installing escalators in the LIRR terminal, 2019

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Some of the 47 escalators that carry customers through Grand Central Madison are 182 feet long.

Laying floor directionals, 2022

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Grand Central Madison is designed with passive wayfinding, which means it is integrated into the built environment. Here, a worker is installing a street exit indicator into the floor.

Long Island: The Main Line gets a third track

The 95-mile Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) Main Line runs from Long Island City in Queens to Greenport in Long Island. Five branches of the railroad split from the Main Line, including the Port Washington, Port Jefferson, and Oyster Bay.

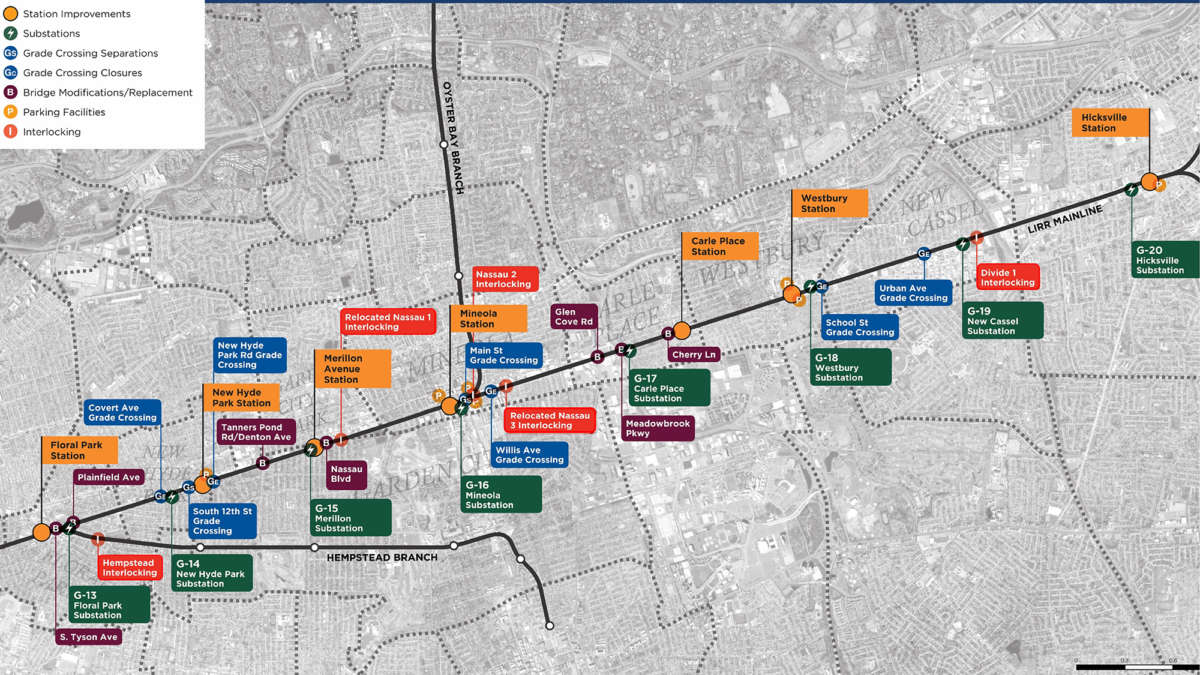

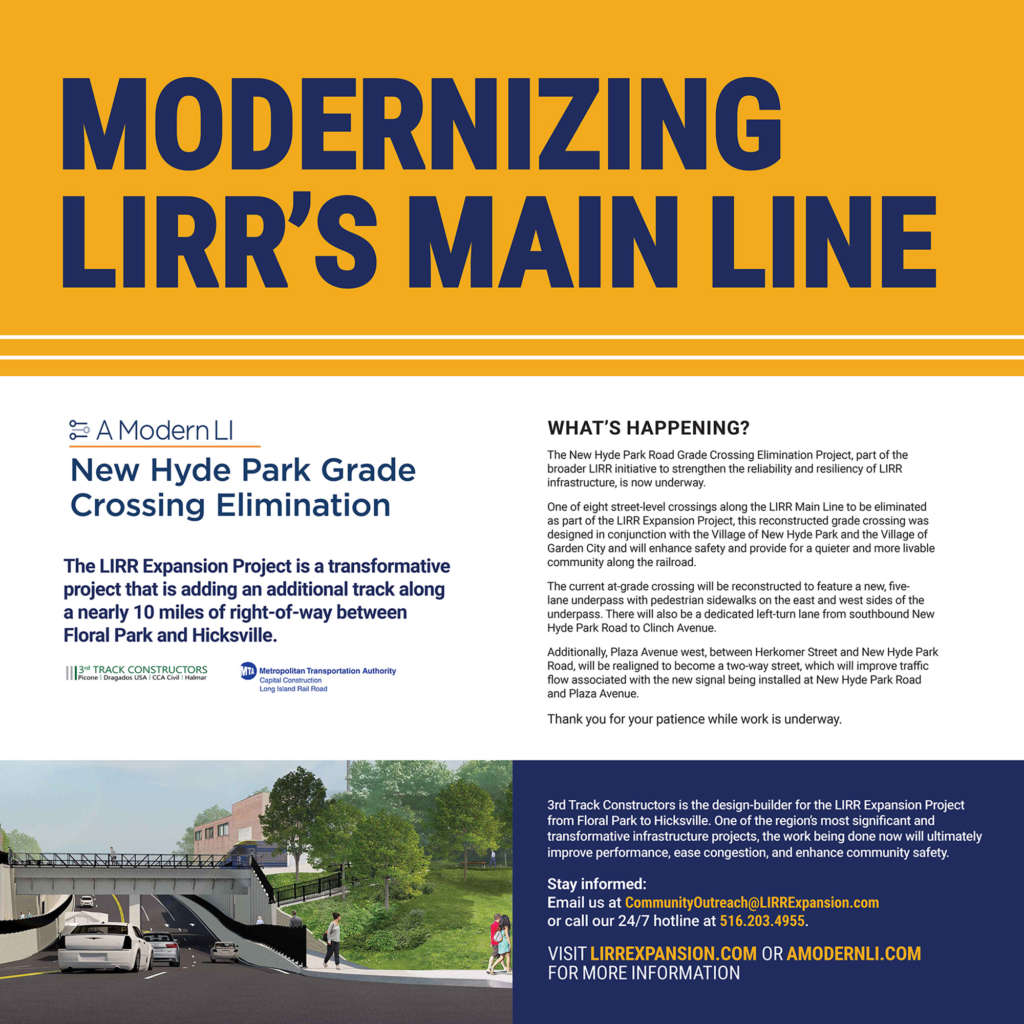

The LIRR Expansion Project took 4 years to lay more than 10 miles of railroad track between Floral Park and Hicksville. This work included eliminating grade crossings, adding parking structures, and building pedestrian crossings over trackways. Groundbreaking was in September 2018 and the project was completed in October 2022.

The LIRR Expansion Project is part of a larger group of modernization projects the LIRR has undertaken in recent years to improve infrastructure all over its service area in preparation for East Side Access and the new terminal at Grand Central Madison.

LIRR Expansion Project overview, 2018

The idea to add a third track to the LIRR Main Line wasn’t a new one: it was first proposed in the 1940s.The project as built includes everything from the cosmetic (such as stations being refreshed) to the electrical and signal systems being updated and improved.

New Hyde Park notice, 2020

Informational campaigns let residents know exactly what was happening to their train stations.

8 grade crossings – places where train tracks were at street-level – were eliminated or changed for the LIRR Expansion Project, which will help ease traffic congestion and reduce accidents.

Queens: A new platform for Jamaica Station

Platform F under construction, 2019

Photograph by Trent Reeves

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Jamaica Platform F is the first of several planned improvements to Jamaica Station. It was built to enable more frequent service between Jamaica and Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn.

Staircase to Platform F, 2020

Photograph by Trent Reeves

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Future work at Jamaica will include extending all platforms to accommodate 12-car trains, adding two new track routes, installing high-speed switches, and an overhaul of the electrical and signaling systems.

Grand future

Once Grand Central Madison is open, customers can get to Long Island from both the East and West sides of Manhattan. Customers going to Pennsylvania Station have been enjoying the new Moynihan Train Hall since 2021. The opening of Grand Central Madison marks the beginning of a new era in rail travel and sets the stage for even more improvements in the future.

Bird’s-eye view of the 50th Street Commons, 2014

Photograph by Rehema Trimiew

Courtesy MTA Construction and Development

Located on 50th Street between Park and Madison Avenues, this 2,400 square foot “pocket park” located next to a ventilation shaft for Grand Central Madison.

Passenger concourse, 2022

Artwork by Kiki Smith

Photograph by Anthony Verde

© Kiki Smith, Grand Central Madison. Commissioned by MTA Arts & Design.

The passenger concourse has a combination of traditional wayfinding (track numbers and arrows) and passive wayfinding in the floors.

Passenger concourse , 2022

Artwork by Kiki Smith

Photograph by Anthony Verde

© Kiki Smith, Grand Central Madison. Commissioned by MTA Arts & Design.

Cool colored glass tiles and white marble allow light to flow through the space.

Detail of A Message of Love, Directly from My Heart unto the Universe, 2022

Artwork by Yayoi Kusama

Photograph by Kerry McFate

Fabricated by Miotto Mosaics Art Studios

Commissioned by MTA Arts & Design and New York City Transit

©YAYOI KUSAMA

Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, David Zwirner

Yayoi Kusama’s nearly 875 square foot boldly colored mosaic on the Madison Concourse, between 46th and 47th streets features iconography from the artist’s work that is both figurative and abstract.

The Water’s Way, 2022

Artwork by Kiki Smith

Photograph by Anthony Verde

© Kiki Smith, Grand Central Madison. Commissioned by MTA Arts & Design.

Kiki Smith drew on the natural world of Long Island to create her pieces, which total over 1400 square feet.

Detail of Go, 2020

Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

Photograph courtesy of Public Art Fund

Go is Kehinde Wiley’s first permanent installation in the stained glass medium. It greets travelers at the 33rd Street entrance to Moynihan Train Hall.