Meet the BU cars, the oldest operational cars in the Museum’s fleet!

The New York Transit Museum has three BU cars: 1273 (built 1903-4), 1404 (built 1908), and 1407 (built 1908).

Although their current home is underground in the Museum’s Court Street subway station, from 1918 onward, these cars were only used on elevated lines. BU’s are composite cars, which means they have wooden bodies over reinforced steel frames. Like all elevated cars in the Museum’s collection, the roofs have been lowered to fit in the Court Street station.

When on the platform at Court Street, you can sit on the rattan seats, look at the reproductions of advertisements riders would have seen when the cars were in service, and even ring the bell by the exit doors!

BU cars on a July 4th fan trip, 1980

Photograph by Ralph Curcio

New York Transit Museum Ralph Curcio Collection

2016.12.1.21.11

What is a BU car?

BU cars are so named because the Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad was one of the last companies to operate them, and it’s a generic term used to describe all of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT) gate cars used on the elevated lines. Gate cars were designed with open platforms at each end of the car, and a trainman, situated between each pair of cars, was assigned to open or close these gates when passengers boarded or alighted the train. Several different companies manufactured BU cars, but 1273 was built by the Laconia Car Company in New Hampshire, and 1404 / 1407 were bult by the Jewett Car Company in Ohio.

BU cars are just over 49 feet long, and 8 feet 8 inches wide. They are 12 feet high and weigh over 57,000 pounds.

Wooden cars similar to these were used on the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) elevated lines and were called “Manhattan Elevated” cars.

The interiors of most elevated cars in New York and Brooklyn looked similar to this, with rattan seat cushions, leather straps, and bare incandescent light bulbs.

Interior of a Pullman-built BU, 1929

New York Transit Museum Vincent Lee Collection

2005.61.35

What was the Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad?

The Brooklyn Elevated Railroad was incorporated in 1885, and the company operated four elevated lines in Brooklyn, parts of which are still in use by the subway of today. Those lines were:

- Lexington Avenue Line (which ran from the Brooklyn Bridge to Cypress Hills)

- Myrtle Avenue Line (which ran from Sands Street in Downtown Brooklyn to Myrtle-Wyckoff Avenues in Bushwick; some portions are now the M line)

- Broadway Line (which ran from Cypress Hills to Williamsburg; some portions are now the J / M / Z lines)

- Fifth Avenue Line (which ran from the Brooklyn Bridge to 65th Street in Sunset Park)

In 1899, the Brooklyn Elevated Railroad went bankrupt and became the Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad, which was controlled by the BRT.

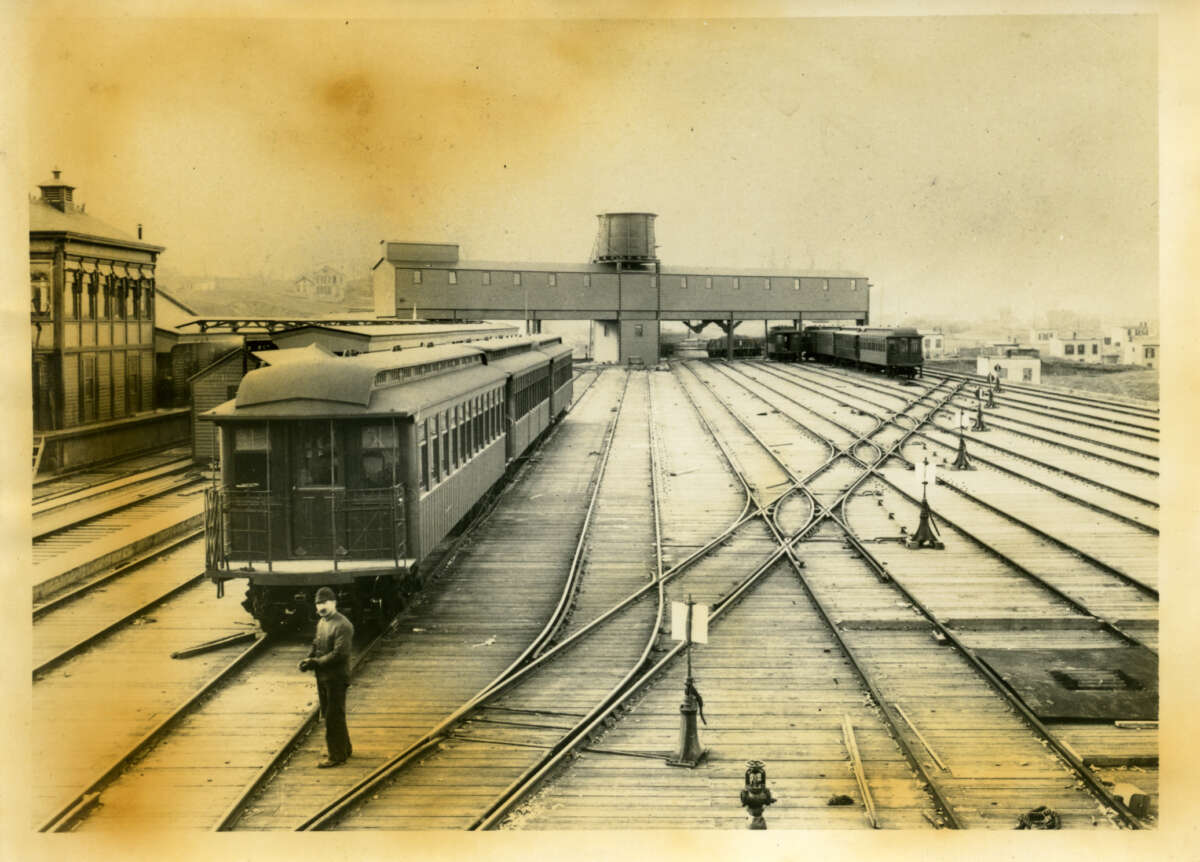

BU cars in the Union Depot of the BRT Fifth Avenue Elevated, c. 1890s

New York Transit Museum Richard C. Carpenter Collection

2010.29.10

Why aren’t there wooden cars in the subways today?

The only time you can experience BUs in motion is when the Museum takes them out on excursions such as the Parade of Trains. According to safety regulations, wooden cars of any kind are not permitted to carry passengers inside subway tunnels.

While composite cars made of wood and steel were among the first kind of cars to roll through the original subway tunnels in 1904, the idea to build all-steel subway cars was already forming at the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) and the BRT. Why? Alexander Cassatt, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) was building some Hudson River tunnels around the same time as the IRT was building the subway and felt that wooden cars posed a fire hazard. He pushed for all-steel cars on the PRR. Cassatt asked his chief engineer, George Gibbs, to offer his services to the IRT and help them build an all-steel subway car. That way, Cassatt could use the IRT as a proof of concept for a steel car, without spending PRR money.

Because designing subway cars takes a long time, the first cars in the subway were a combination of wood and steel. In 1903, Gibbs was able to have an all-steel prototype car made. Modifications continued to be made to make the cars lighter and sturdier until the IRT’s first all-steel cars, called Hi-Vs, made their debut in 1904 (shortly after the first subway line opened) and began to replace that company’s composite cars.

By 1910, the PRR had over 300 all-steel cars in service, which set the tone for adoption on other railroads. Additionally, several fires and accidents in other cities hastened the demise of wooden cars in rail service. Each time there was a fatal accident involving wooden rail cars, pressure increased to remove them from service.

With the start of a period known as the Dual Contracts era – when both the BRT and the IRT signed contracts with New York City to expand subway service – the BRT began providing subway service for the first time. Knowing that the IRT was already improving its fleet of Hi-V steel cars, the BRT hired an engineer to design a steel car for their subways. His name was Lewis B. Stillwell. In 1912, he had completed designs for the car, and in 1913 put a model of the proposed design on display in Brooklyn. The BRT’s first all-steel cars, called AB Standards, started rolling in 1915 and began replacing the BU cars.

While new steel cars began filter into the BRT fleet, the elevated lines were still served by composite cars. However, the evolving system, as riders experience today, began to develop routes that were both above and below ground. On the evening of November 1, 1918, a five-car train comprised of cars similar to the Museum’s BUs was involved in the deadliest train crash in the New York City subway’s history: the Malbone Street wreck. Over 100 people were killed and 250 people were injured. Although composite cars were not widely used at this point, there was a renewed push to eliminate them from service altogether. While complete elimination did not happen, other safety measures, such as trip arms, speedometers, and better signals were implemented to avoid another catastrophe of this magnitude.

The last composite cars in use in the New York City subway were Q-Types, on the Myrtle Avenue Elevated. They were officially retired in 1969, and you can see one on the Transit Museum’s platform at Court Street.

BU cars in service on the Myrtle Avenue Elevated, 1950

Photograph by Wigorot Lundin

New York Transit Museum Lundin Collection

2004.20.6.478

Hudson Street Station on the BMT Fulton Line, 1942

New York Transit Museum Lundin Collection

2004.20.15.115

Why are there all these old ads in these cars?

The ads in the BU cars are representative of what passengers would have seen while they were in service during the 1900s-1940s. Some of the ads are for products that seem funny to us now, and some are for things we might still have around the house. Some of the brands are recognizable, and some are long forgotten. Advertising has always been present in transit systems, and for good reason: a captive audience that is always growing. As public transportation became more popular, companies knew that one of the best ways to let people know about their products was by putting ads in streetcars, elevated and subway cars, and later, motor buses. Advertisements for products shared space with appeals for courtesy, as well as service notices.

Ivory soap advertisement, c. 1930s

New York Transit Museum Collection

2002.36.5