Malbone Street Wreck

November 1st marks the anniversary of the Malbone Street Wreck, the worst subway accident in the history of New York City. As we remember the tragic events of that day, we honor those who lost their lives and the families who were affected. We also recognize that disasters such as this can be the catalyst for change and improvements to help prevent such tragedies from happening again.

What Led to the Disaster?

During the 1910s, the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) was in contract with the City of New York to construct new subway lines and upgrade older lines in partnership with the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT)–a time in transit history known as the “Dual Contracts Era.”

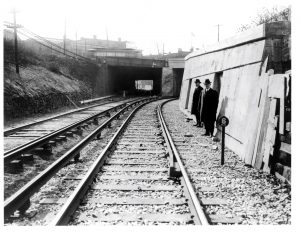

On September 25, 1918 a newly-constructed tunnel under Malbone Street opened to accommodate the growth of the subway system. The new tunnel, which would allow trains to pass over a new connection for the subway, was constructed with a sharp S-curve. Train operators were instructed to travel at a maximum of 6 mph to ensure safety.

At the time the tunnel opened, there was strife between the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company and the union known as the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers. When negotiations failed between the two, the Brotherhood called on motormen and motor switchmen to strike on November 1, 1918.

The Accident

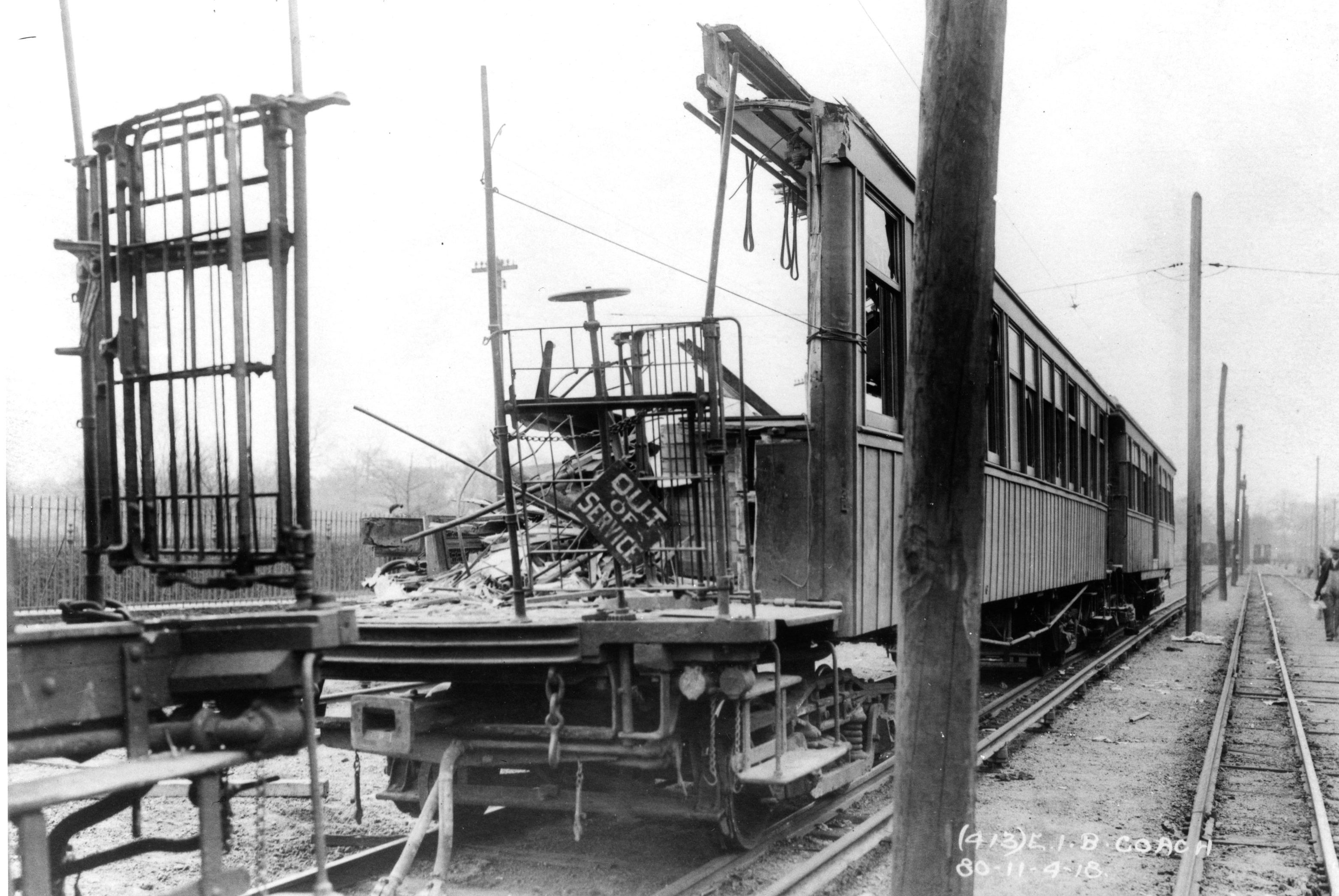

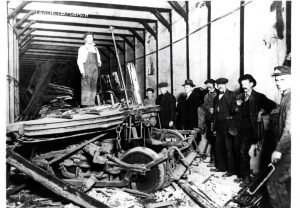

To prevent disruption in service, the BRT placed inexperienced workers in operating roles, including a young dispatcher named Edward Luciano who was pressed into service as a motorman on a Brighton Beach-bound train, though he had never previously operated a passenger train. The wooden five-car train was crowded with 650 passengers, rushing south at an accelerated speed on the tracks of today’s Franklin Ave Shuttle. At 6:42 pm, the train approached the S-curve in the tracks at approximately 30 mph, 24 mph over the speed limit. The wooden train derailed, resulting in the deaths of nearly 100 people. It remains the worst subway accident in New York City history.

The accident was caused by several factors: In addition to the motorman’s inexperience and the excessive speed of the train, the train cars themselves were not configured properly. Trains of that era featured two types of cars: a motor and a trailer. Motor cars were about twice as heavy as trailer cars and their weight was distributed evenly. Trailer cars were lighter with most of their weight on top. Normally, trains were configured to alternate motor and trailer cars to provide stability. But Luciano’s train was configured so that trailers and motors were next to each other, probably because an inexperienced motor-switchman incorrectly coupled the train in the yard before its run. The train was unstable, which led it to derail when it sped into the sharp curve.

After Affects

Edward Luciano and five high-ranking members of the BRT Company were brought to trial as a result of the Malbone Street accident. All six were eventually acquitted of the charges.

Perhaps the most significant impact of the Malbone Street wreck was that the tragedy fundamentally altered the transit system’s approach to the safety of crew and passengers. The wreck led to important decisions such as: stricter training and requirements for motormen; phasing out of wooden train cars in subway tunnels by replacing them with composite wood and steel cars and ultimately fully metal-bodied cars; improving signal systems; and installing onboard train controls to guard against excessive speed.

Malbone Street was renamed and is known today as Empire Boulevard. And while the tragic events of that day have faded from public memory, transit workers ensured that one powerful reminder would remain. The switch that restored power to the tracks at Malbone Street one hundred years ago is still present at the nearby Prospect Park Electrical Substation.

To explore more mass transportation history, plan your visit to the New York Transit Museum.